Reverse-engineering the Coles mobile app

Let’s reverse-engineer a supermarket’s mobile app so that I can get my transaction history.

I have an old project called up_woolies that proposed integrating supermarket e-receipts with my banking app. No longer would I stare at a bank transaction & wonder if that purchase included milk & eggs. You can read more about it here but, in short, it uses the APIs for Up Bank & the supermarket chain Woolworths to associate bank transactions with grocery e-receipts.

The project relied on access to a customer’s transaction history: the list of digital receipts containing the purchased items, date & location, etc. for every transaction made in-store or online. Woolworths collects & stores this information via its loyalty program, Everyday Rewards, & allows customers to browse their transaction history for up to the last several months.

Despite the natural desire to support the other major Aussie supermarket chain, Coles, at the time, did not provide customers with that information with their loyalty program, Flybuys. And so, the project shipped, half-finished in my mind. Nothing more could be done.

Well, seasons pass & I have recently learnt that Coles has made transaction history available to customers via their mobile app. This is great news! But, a challenge emerges: how do I discover & replicate the API request that the app is making? Mobile apps, put simply, operate quite differently than traditional websites & I have limited experience with them.

I eventually cracked the code & here’s the technical breakdown of that journey.

The goal

The goal is to find the API endpoint that the Coles App communicates with to retrieve a customer’s transaction history. If I was able to view this data from the Coles website, then it would be trivial. I could repeat the same steps I took with Woolworths for up_woolies:

- Open browser’s developer tools, e.g. “F12” Chrome’s DevTools.

- Record browser’s network traffic from the

Networktab. - Navigate around the target website.

- Cherry-pick requests of interest; e.g.

GET .../me/profile.json. - Test replicating requests with an API developer tool, e.g. Postman, or Hoppscotch.

I’ve skimmed over authentication, but those are the basics of web scraping.

The same cannot be done for Android apps. There is not Chrome DevTools or equivalent. Apps are intrinsically different from websites in how they are developed, built & run. This allows apps to be isolated from one another for security & privacy - messenger cannot listen to your banking app, for example.

However, a sophisticated user could still find ways to reverse-engineer apps. Initially, I could think of only two options forward:

- Decompile the app’s code

- Intercept the app’s network traffic

Decompilation

Decompilation is a gamble. It produces a distorted & often incomplete imitation of the original source code. See, Android apps are commonly developed in Java & Kotlin, beautiful human-readable code languages, that are then compiled into machine-executable bytecode (Davlik .dex) & bundled into an APK (Android Package Kit .apk) archive. A lot of the metadata is lost: function/variables names, in-code comments, etc. This information cannot be recovered, but the decompiler tries its best & applies placeholder names & structure. It is a gamble that there will be useful code snippets in the messy haystack.

APK files

We’ll need the Coles App’s APK file to start. This is the file that’s used when downloading & installing apps from the Google Play Store. The Google Play Store does not support the direct download of APK files to a non-Android device, such as a PC. However, there are third-party sites that do: APKPure, APKMirror & APK Downloader. These sites tend to serve PC gamers who wish to run Android games on emulators & virtual devices. While that appears to be their core demographic, they do host the APKs for almost all available apps. I say almost because I suspect Coles has actively taken steps to remove their app from each one of these popular third-party sites.

While a nuisance that we cannot download the app directly, this is not a showstopper. App APK Extractor & Analyzer, as the name suggests, can export the APK of any installed Android app, without the need for root access. The exported APK file can then be transferred off device using the Android Debug Bridge (adb) or any other method.

Decompilers

There are a handful of open-source options for decompiling APKs, & I tried these few:

- decompiler.com: An online decompiler.

- Apktool: CLI tool for decompiling & building APKs. Decompiles to Smali.

- APKLab: A VSCode extension built on top of several other tools. Didn’t deliver for me.

- jadx: 👑 A decompiler with a GUI built for digging through the Java & Smali source code.

I favoured jadx. Its GUI supports code-navigation features that I feel are requirements for sifting through noisy decompiled code: jump-to-declaration, find-usage, full-text-search. Common features that VSCode/APKLab & IntelliJ IDEA failed to work with such a messy code base.

Source code findings

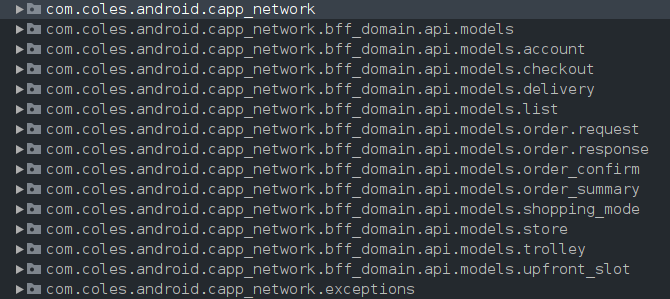

I’ve moaned about decompiled code enough, so allow me to show you what it’s like. Decompiling the Coles App produced 24,715 files across 1,216 directories, most of which were given meaningless placeholder names by the decompiler; a, a0, a00, a1, etc. That being said, the contents of the com/ directory

remained human-readable & the core of the Coles App could be found under com/coles.android.

A keyword search across all files for /api returned a snippet of interest: a method containing an API endpoint path v3/api/1/transactionHistory & return type TransactionListResponse. The import statements of this file reference a directory containing the app’s larger set of API requests & return types.

This is the closest I’ll get to API documentation.

Another keyword search for coles.com.au led to a ReleaseLocalConfigKt.java file. It contained the app’s runtime configuration settings: API base URLs, Coles & Flybuys authentication endpoints, certificates, feature flags, etc. The API base URLs are useful & together I can take an educated guess at the full API path for transaction history:

apigw.coles.com.au/digital/colesappbff/v3/api/1/transactionHistoryThis is so close. What is needed to complete the picture is an understanding of the authentication method that the request requires. The developers are likely using some common method, such as a short-lived session token stored in the request’s header. But what is that header key called, where is it stored, & is that even the case?

One shot in the dark is to attempt the same authentication method that the website uses & see if this works for the app’s request. We can see, from the decompiled code, that the authentication endpoints mirror those seen in the network traffic for the website - both app & website authenticate the user the same way &, for the website, a session token is stored in the browser’s cookies. I attempted to use this token for this new endpoint - but it failed. That’s fine; this new endpoint for transaction history has a different API path compared to those seen in most of the website client’s requests so it’s not unthinkable that it requires a different authentication method.

What would make life easier is if I could see the network traffic…

Intercepting app traffic

Android apps operate fundamentally different from websites in the browser. They run in sandboxed environments that limit direct access to their network traffic for security & privacy reasons. App developers have tools to inspect their app’s traffic, namely Android Studio’s Network Inspector, but its scope is limited to one’s own source code during development & testing - not third-party apps.

Intercepting, decrypting & inspecting network traffic for an Android app will solve most of our problems but is significantly difficult. Done correctly, it can be an equivalent to Chrome’s DevTools &, in truth, this should have been the first thing to try. It’s also considered fairly offensive in cybersecurity terms, perhaps you’ve heard of Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) Attacks?

An app’s network traffic can be intercepted if the device’s network is routed through a VPN or proxy we control. This traffic will still be HTTPS encrypted, but if the device also trusts the MitM’s Certificate Authority (CA) then we can decrypt & inspect the traffic. User-installed CA certificates aren’t generally trusted by apps for this specific reason. System-level certificates, on the other hand, come preinstalled on Android OS & are app-trusted by default. Since these certificates are well-trusted, injecting certificates into the system-level certificate store requires root user access.

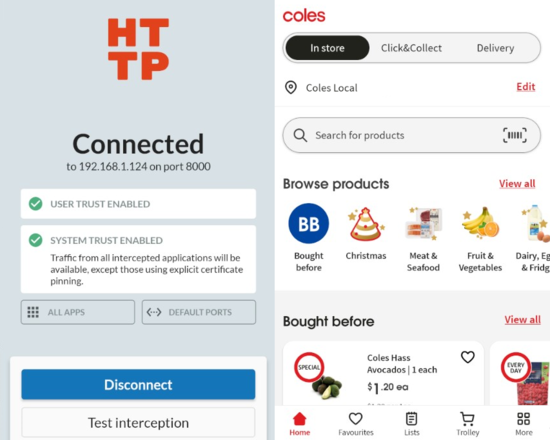

HTTPToolkit

HTTPToolkit is a godsend. It is a versatile network traffic inspector that will play the role of our MiTM proxy, & has great docs guiding you on this subject matter. Since I need a rooted device, I’ll run a virtual Android 13.0 (Google APIs) using Android Studio’s Virtual Device Manager. Setting up HTTPToolkit with the device via adb will install its companion app, inject its root CA certificate into the device’s system-level certificate store, & establish a VPN for select apps’ network traffic.

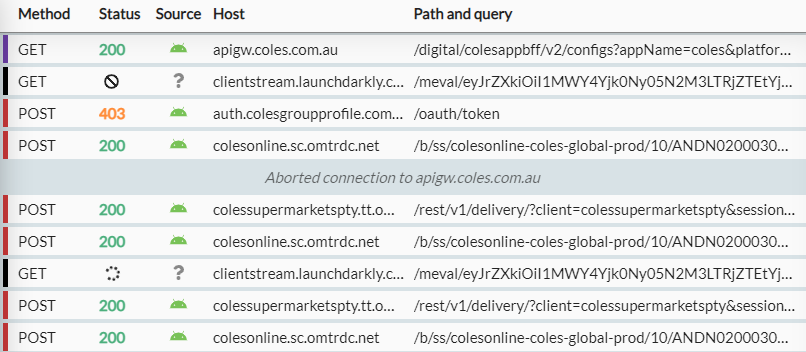

At first glance, everything seems to be working. HTTPToolkit displays the API requests & data fetches as I open Coles App. I can login successfully - but that is where it ends. All other requests for app-specific data, such as products or promotions, show “failed to connect”. In the network logs, I can see that requests to apigw.coles.com.au are failing.

Certificate Pinning

Security-conscious developers can attempt to prevent network interceptions by employing a security approach called certificate pinning. This is useful when you believe that a device may be compromised, say the system-level certificate store, for example. Instead of trusting any of the device’s certificates, developers can hardcode trusted certificates for traffic encryption into their app’s source code.

Certificate pinning can be circumvented.

Frida is another powerful “toolkit for developers, reverse-engineers, and security researchers”. HTTPToolkit has a detailed guide on how Frida can be used to remove certificate pinning implementations from some widely-used libraries.

=== Disabling all recognized unpinning libraries ===

[+] javax.net.ssl.HttpsURLConnection setDefaultHostnameVerifier

[+] javax.net.ssl.HttpsURLConnection setSSLSocketFactory

[+] javax.net.ssl.HttpsURLConnection setHostnameVerifier

[+] javax.net.ssl.SSLContext init(KeyManager;[], TrustManager;[], SecureRandom)

...

a long list of libraries

...

== Certificate unpinning completed ==Unfortunately, this didn’t work right out of the box. But, by luck, one of the error messages from Frida showed certificates that I so happened to recognize from when I was sifting through the decompiled code. They are the same certificates from the app’s configuration settings file. Naively, I think to myself, could I just slap the MitM CA cert in there & build a modded version of the app?

!!! --- Unexpected TLS failure --- !!!

SSLPeerUnverifiedException: Certificate pinning failure!

Peer certificate chain:

sha256/MByFQRuycd4oLyuYzdy5NBR5S53wR5P+S6iy1TaPmjo=: O=Mockttp Cert - DO NOT TRUST,L=Unknown,C=XX,CN=apigw.coles.com.au

sha256/7TPYizy1/s4g1+YiEOPBaCnfQw8gqiTyF4dEpJ88Ui8=: O=HTTP Toolkit CA,C=XX,CN=HTTP Toolkit CA

Pinned certificates for apigw.coles.com.au:

sha256/it1PudsiUlhRdxX/qmL7T8zRBrqC5GTdCVr+Un4RKeQ=

sha256/t/4jXnw21V/u+TVAfaiGmKBHb06odSEzsRQsvrPj7k4=

Thrown by v80.o->a

Already patched - but still failing!

=> Fallback OkHttp patch

=> Fallback OkHttp patchThe workaround

The Coles App appears to use a custom implementation of certificate pinning. This prevents popular open-source security tools, such as Frida, from disabling its implementation. However, Frida’s logs its failure along with the pinned certificate fingerprints used by the app. It’s noted that these are the same found in ReleaseLocalConfigKt, the app’s configuration settings, from inspecting the decompiled code. Replacing these certificates with those used by HTTPToolkit & recompiling to create a modded APK file could be enough to decrypt intercepted app traffic.

- Decompile the Coles App APK using

apktoolCLI tool. - Inject the SHA-256 fingerprint of HTTPToolkit’s CA certificate alongside the existing pinned certificates within

ReleaseLocalConfigKt. - Rebuild the modified decompiled code to an APK using

apktool. - Sign the APK using

uber-apk-signer. - Install the APK onto a virtual Android device.

- Run HTTPToolkit & intercept app traffic.

Edit from the future: while reproducing the steps, I discovered that I didn’t need to mod the APK file. Running HTTPToolkit followed by Frida - configured to use HTTPToolkit’s CA certificate - appeared sufficient to intercept & decrypt the app’s traffic.

The results

Mission accomplished! We can see the exact API request for transaction history in detail, confirm that it is to the API URL that we guessed earlier, & learn that the authentication method is a bearer token. I knew very little about reverse-engineering Android apps or intercepting app traffic before I started this. It goes to show how amazing the open-source community is to have developed & supported the tools that got us here.